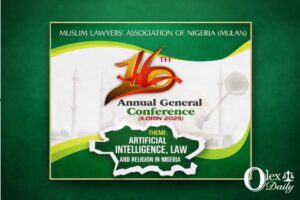

Artificial intelligence has moved from novelty to infrastructure within legal practice. Research platforms, drafting assistants, analytics tools, and transcription software now shape how legal work is organised, prioritised, and delivered. Their appeal is obvious: speed, efficiency, and scale. Their deeper consequence is less visible but more profound. They test how much of legal judgment can be mediated by machines without weakening the profession’s claim to authority.

For law, artificial intelligence is not merely a technological development. It is a professional question. The central issue is no longer whether AI can be used, but whether it can be used without eroding the ethical foundations upon which legal practice depends. The Nigerian Bar Association’s 2024 Guidelines on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Legal Profession reflect this concern. They do not treat AI as a licence for delegation. They reaffirm that responsibility, judgment, and accountability remain human obligations.

Assistance, Not Substitution

At the heart of ethical AI use lies a principle that is simple but non-negotiable: artificial intelligence may assist legal work, but it cannot substitute legal judgment. Drafting, research, pattern recognition, and data processing may be delegated to machines. Advice, opinion, and responsibility may not.

Every AI-assisted output—whether a research summary, contractual clause, or litigation forecast—remains the lawyer’s work in law. The presence of software does not dilute authorship; it sharpens it. Where judgment is mediated by algorithms, the duty of independent scrutiny becomes heavier, not lighter. AI does not remove responsibility from the lawyer. It concentrates it.

Oversight as Ethical Discipline

Ethical use of artificial intelligence begins with supervision. No AI-generated material should be relied upon without independent verification for accuracy, relevance, and consistency with Nigerian law. Errors produced by an algorithm do not belong to the algorithm in professional or disciplinary terms. They belong to the lawyer who relied upon them.

This principle carries direct doctrinal consequences. Where AI-assisted advice proves defective, liability will be assessed by reference to professional conduct, not technological sophistication. Negligence, breach of duty of care, and disciplinary misconduct will turn on whether the lawyer exercised adequate oversight. Software does not insulate responsibility. It exposes the standard by which responsibility will be judged.

Confidentiality in a Data-Driven Environment

Confidentiality remains non-negotiable. Many AI tools process client documents, communications, financial records, and sensitive personal data. Their use therefore implicates core professional duties alongside statutory obligations, particularly under the Nigeria Data Protection Act, 2023.

The ethical question is not whether a tool is convenient or widely used, but whether client information is securely stored, lawfully processed, and protected against unauthorised access. Free or uncertified AI systems may appear efficient, but their deployment in client matters carries disproportionate risk. Convenience cannot justify exposure where confidentiality is foundational to trust.

Disclosure and the Preservation of Trust

As AI tools increasingly shape legal services, transparency becomes an ethical expectation. Where the use of artificial intelligence materially affects the nature, quality, or outcome of legal work—and where a client would reasonably expect to be informed—disclosure is required.

This is not a demand for a technical explanation. It is a demand for honesty. Disclosure preserves trust by aligning client expectations with professional conduct. Silence, where transparency is warranted, risks ethical breach not because AI was used, but because responsibility was obscured.

Doctrinal Stress Points Revealed by AI

Artificial intelligence exposes pressure points within established doctrines of professional responsibility. These stress points are further illuminated by the ethical challenges outlined:

- Competence: Lawyers must understand the tools they use well enough to assess their limits and risks.

- Supervision: Delegation to AI requires oversight no less rigorous than delegation to junior counsel or support staff.

- Confidentiality: Data-driven systems amplify exposure where safeguards are weak.

- Negligence and Discipline: Reliance on flawed AI output will be judged by professional standards, not technological novelty.

These are not speculative concerns. They are present realities. Artificial intelligence does not create new duties so much as it tests whether existing duties can withstand delegation without erosion.

Cultural and Ethical Limits of Automation

Certain areas of legal practice—family law, inheritance, customary matters, and religiously inflected disputes—are deeply embedded in moral, cultural, and communal context. In such domains, automated decision-making tools must be approached with particular restraint.

Efficiency cannot substitute for understanding. Organisation cannot replace discretion. Artificial intelligence may assist clarity and structure, but it cannot displace the ethical reasoning that underpins just outcomes in socially sensitive matters. Where law is intertwined with moral meaning, human judgment remains indispensable.

Institutional Responsibility, Not Individual Prudence

The ethical use of artificial intelligence is not merely a matter of individual caution. It is an institutional responsibility. Without shared standards and collective discipline, the profession risks uneven practice, diminished public trust, and reactive regulation driven by crisis rather than foresight.

By insisting on human oversight, doctrinal accountability, and ethical restraint, the legal profession preserves authority over the tools it adopts. Technology should not silently govern professional conduct. It must remain governed by it.

Governing Innovation Without Surrendering Judgment

Artificial intelligence offers genuine benefits to Nigerian legal practice. Used responsibly, it can improve efficiency, expand access to legal services, and strengthen analytical capacity. Used carelessly, it can undermine confidentiality, distort judgment, and expose lawyers to serious professional risk.

The task before the profession is therefore not rejection but governance. Innovation must proceed without surrendering responsibility. That balance is achieved not by resisting technology, but by insisting that judgment, accountability, and ethical discipline remain non-delegable.

Artificial intelligence will continue to evolve. Whether legal authority evolves with it—or quietly recedes—will depend on how firmly the profession insists that the machine remains an assistant, not an author, of legal judgment.