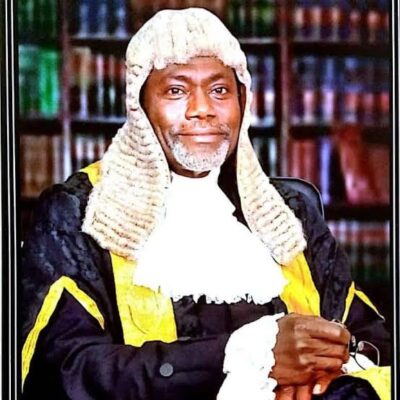

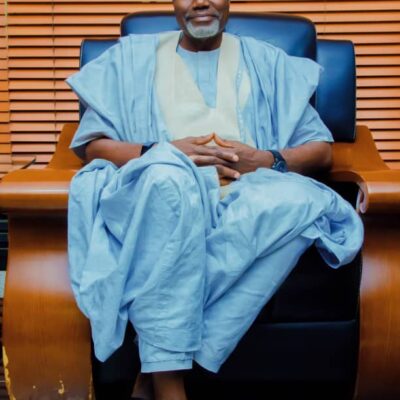

Artificial Intelligence is no longer science fiction. From self-driving cars to predictive text, it has seeped into daily life, subtly rewriting the rules of engagement across industries. But what happens when these algorithms venture into the courtroom? At the 16th Annual General Conference of the Muslim Lawyers Association of Nigeria (MULAN) 2025, Prof. Yusuf Ali, SAN, presented a compelling paper that challenged the legal community to confront a future rushing at it faster than it’s willing to admit. Far from a distant threat or passing fad, AI is now poised to fundamentally alter the way Nigerian lawyers work, think, and serve justice.

A Paper That Pulled No Punches

Prof. Yusuf Ali SAN’s presentation was a study in balance—neither alarmist nor blindly optimistic. While acknowledging AI’s capacity to enhance legal research, streamline document review, and assist in case prediction, he made it abundantly clear: the Nigerian legal profession is dangerously unprepared. “The law may be slow to change, but technology is not waiting for anyone,” he warned.

His paper laid bare the structural, infrastructural, and cultural weaknesses hampering Nigeria’s ability to integrate AI safely and equitably into legal practice. Unlike keynote addresses that often stir hope, the learned Silk’s presentation demanded sober introspection.

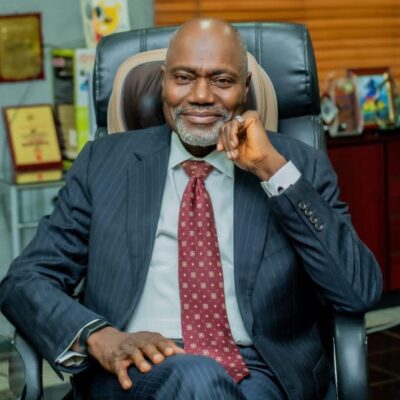

The Real Challenges No One Can Ignore

The learned silk identified ten critical obstacles that stand between Nigerian lawyers and effective AI integration. From inadequate digital infrastructure and prohibitive licensing costs to cybersecurity risks and a dire lack of AI literacy among practitioners, the list reads like a state-of-the-nation diagnosis for legal tech readiness.

Perhaps most damning was his observation that AI solutions currently being introduced into the Nigerian market are largely foreign-built, designed for the procedural peculiarities of U.S. and U.K. jurisdictions — with little regard for Nigeria’s distinctive legal doctrines, procedural rules, or data realities. Without local innovation and investment, the country risks becoming a digital colony in legal tech.

“It is not the machine that will take your job — it is the lawyer who knows how to use it that will.”

NBA’s Moral and Professional Mandate

Prof. Yusuf Ali didn’t stop at problems; he sketched out the proactive role the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) must assume if the profession is to survive with its ethics, relevance, and public trust intact.

He advocated for urgent legal education reforms, the institutionalization of AI literacy in continuing legal education (CLE) programs, strategic partnerships with tech innovators, and—crucially—the enactment of a robust regulatory framework to govern the use of AI in legal services.

The NBA’s recently released Guidelines for the Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Legal Profession in Nigeria garnered praise as a commendable first step, but a learned silk was clear: guidelines are not enough. Nigeria needs enforceable laws on AI accountability, malpractice, data protection, and algorithmic fairness.

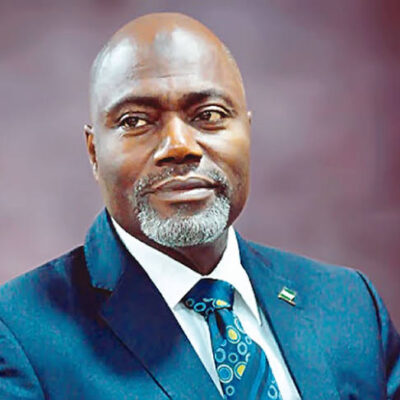

Lawyers vs. Machines: A Debate Far From Settled

One of the most striking parts of Learned Silk’s paper was his reflection on the emotional, cultural, and ethical resistance to AI within Nigeria’s legal community. In a profession steeped in tradition, where the human touch, discretion, and streetwise intuition are valued as much as black-letter law, the notion of ceding ground to machines feels like sacrilege to many.

Yet the prof. punctured the familiar panic narrative with nuance. AI, he argued, isn’t coming for the jobs of brilliant advocates or innovative legal thinkers — it’s coming for those unwilling to evolve. The real threat lies not in the machines, but in human complacency.

The Lawyer of Tomorrow

The SAN’s closing remarks were a call to reimagine legal practice in Nigeria. He described the future lawyer as not just a practitioner of law, but a digital leader, an ethical compass, and a policy advocate for responsible AI use.

Tech fluency, data literacy, and an understanding of digital rights would no longer be optional extras but core competencies. The Nigerian Bar, the learned silk insisted, must embrace this future boldly — not by abandoning tradition, but by preserving its ethical soul while upgrading its tools and tactics.